In the 2022-23 school year, California began implementing the Universal Meal Program to combat child hunger and improve academic outcomes by requiring public schools to provide two free meals per day to students. While some see the convenience of free meals as a benefit, some see this as coming at the cost of health and quality. Food waste amid the availability of options highlights issues between what the menu offers and the quality of food expected by students.

For example, freshman Kalina Zacarias believes the policy underscores issues of equity. The free meals ensure that a student’s ability to eat at school isn’t dictated by individual circumstances such as financial difficulty.

“I think it’s fair because sometimes parents are too busy to pack lunch, so it’s good that the school provides food for them,” Zacarias said.

While the accessibility of school lunches receives positive reactions from Zacarias, the quality of food often sparks comparisons to prison food–bland, uninspired or made only to fulfill the bare minimum. Despite these criticisms, some students find ways to appreciate the effort made on the part of the administrators for what’s being served.

“I think they try to make it as healthy as possible,” Zacarias said.

For some other students, like freshman Leonardo Foronda, the taste and appearance of lunches have led to dissatisfaction that affirms dismissive comparisons to meals served in correctional facilities.

“Yeah, the food quality… I think it’s similar to prison food… The quality. The taste, I guess. The way it looks,” Foronda said.

In 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was passed, improving federal nutrition programs for low-income school children. A report by the National Library of Medicine, a leading authority in biomedicine, showed that the law had significantly benefited impoverished children, with their obesity rates decreasing by 9% each year.

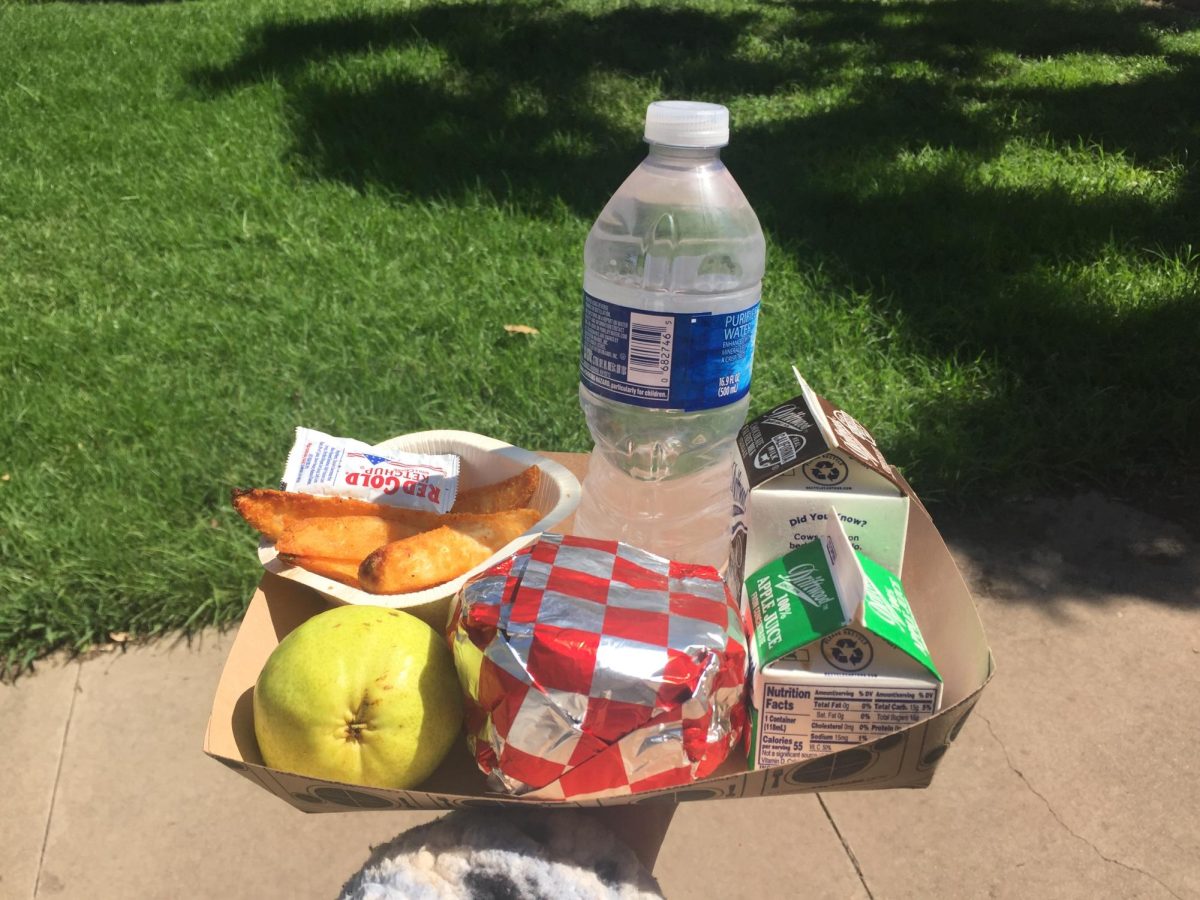

However, despite these improvements and the provision of healthy offerings like fresh fruits (pears or oranges) and vegetables (baby carrots and jicama sticks), some students still feel these inclusions don’t translate into adequate support for their development.

“I would make the food more nutritious. It doesn’t support growth for teens,” Foronda said.

This view is supported when looking at the sodium content in various menu items. For example, beef hamburgers, spicy chicken sandwiches and non-spicy chicken sandwiches contain 1,137.5 mg, 610 mg and 570 mg of sodium, respectively.

The American Heart Association, a leading authority on heart health, recommends an ideal sodium intake of 1,500 mg. In one burger or sandwich, a student can consume half or even more of that, making it difficult for them to maintain a balanced diet.

Even with the common assumption being that school lunches provide convenience at the cost of quality, some students would say their experience defies this popular opinion.

“I honestly think school lunch is pretty good. I usually get the chicken sandwich every day,” Zacarias said.

Still, some students manage to find a middle ground between these two views. For them, the meals are adequate for what they provide, yet still fall short of being a fully satisfying spread.

“The quality isn’t bad, but it’s not great either. It’s like…the food doesn’t have much flavor,” junior Nathan Castaneda said.

The USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service, the federal agency responsible for setting nutrition standards, now requires at least half of the grains in school food products to be whole grains. This means that schools will now use whole-grain buns in their burgers and rice dishes to satisfy the updated nutritional requirements, although some feel this change neglects other important factors of meal satisfaction.

“I feel like there should be more dairy and meat,” Foronda said.

While a variety of meal options is offered, the availability of each item is not ensured. Limited quantities and high demand for certain offerings mean that many popular items run out before many students have the chance to try them.

“Sometimes they run out of certain foods because there are too many students to feed,” Castaneda said.

While the demand for some items leaves students without options, other foods go to waste when students take more than they need or leave food uneaten. This not only reflects inefficiency in the distribution of food at the cafeteria but also the growing food waste problem on campus.

“I think a lot of food gets wasted, and that’s a problem because it wastes a lot of money. That money could be used for other things,” Zacarias said.

According to the Mayo Clinic, renowned for having some of the best medical professionals in the world, drinking water while having meals can improve digestion, prevent constipation, and help lose extra weight by enhancing satiety. Students can recognize the benefits of this firsthand through the bottle of cold water provided in the cafeteria.

“I like that they do that because it lets me drink water whenever I need it,” Castaneda said.

When considering the structure of a school day, lunch break is the time when most students have to destress from their classes. The length of the lunch break can influence how much students can eat, affecting their energy levels for the rest of the day. With 35 minutes for lunch each day, students maintain different perspectives on whether that time is sufficient for numerous activities, such as eating and socializing.

Some students see that the current lunch period provides an ample amount of time for them to take a break from their class schedules.

“Yeah, I’m comfortable with it,” Zacarias said.

However, other students may prefer an extended lunch break to allow for better enjoyment in their meals, such as an additional 15 minutes to move around.

“I feel like 50 minutes would be better,” Foronda said.

California’s school lunch program ensures that all students can get the food they need at no cost, but students have mixed opinions about the taste and nutrition. While some appreciate the healthy options and convenience, others feel the meals could be more appealing or simply do not fully meet their needs for health. Even with progress, school lunches have room to grow.